That anxiety is significant, and it’s been one factor in my not having returned to this blog since I left the class Tuesday night, energized though I was. (The four classes I’m teaching have also complicated just finding the time to write.) Still, even as this anxiety emerged on Tuesday, it was accompanied by an excitement about pushing myself to do something new (blogging) while exploring Whitman. But I also want to try to focus and personalize this semester and my relationship with Whitman.

To do this, I’ve surveyed what other significant elements I’m currently negotiating. Perhaps one of the most exciting for me–and one that’s also tied to new technologies–is the migration of my significant genealogical work (about thirty years’ worth) to the Internet and Ancestry.com in particular. At present I’m immersed in this project–scanning and posting family photos, drawing on on-line census, birth, and death records, completing genealogical trees, and so forth–much of which includes a focus on the nineteenth century. Therefore, at least in part, I’ve set myself the undertaking to put Whitman and his poetry in dialogue with my own ancestors from the era, a process that has seemed, at least at first, incongruous and perhaps a tad futile. I’m hoping, though, that instructive links will develop.

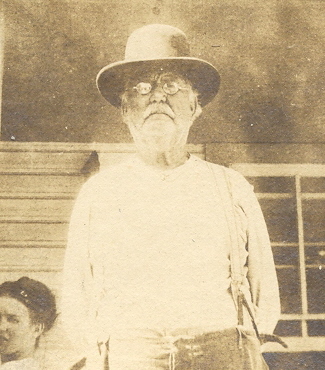

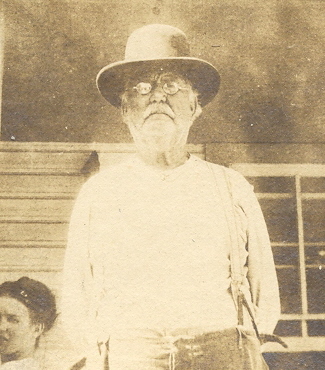

In particular I’m focusing–in part–on a handful of direct male and female ancestors, most of whom had located to north-central Texas, still largely frontier in 1861, in the 1840s and 50s. I hope to devote a fuller identification of these figures later, but for now I’ll focus on James Madison White, known as “Jim.” Born in 1838 in Georgia, he served as a Confederate soldier, married and fathered fifteen children, and died in 1917. As I’ve been thinking of White alongside Whitman since Tuesday, one element that has emerged is the dramatically different number of representations of these two figures. While Whitman has been well- (some might say excessively) imaged, only four images of White seem to have survived. (The growing participation of genealogists on-line, however, gives hope that new personal photo archives may become available and reveal other images.) For White, three of these images come from his old age in the early twentieth century. Therefore, despite his being a generation younger than Whitman, White seems far more typical of most nineteenth-century Americans. Yes, there were photographic images made, but they tended to be rare. Whitman and his imagistic excesses are far more modern, akin to the explosion of images that, as my collecting of photos has suggested, mark most individuals after the 1920s.

But what of the famous 1855 image of Whitman? When doing my image-inclusive first post in class on Tuesday, I immediately replicated that illustration, asserting it just seemed the “right” thing to do. I’d taught that image in practically every class in which I’d taught a Whitman text, dutifully juxtaposing the image against those of Longfellow and Emerson. But the more I thought about that image of Whitman, especially when I juxtaposed it with this image of Jim White from about 1915

the more I realized how stiltedly staged Whitman seems. Yes, he’s refreshingly casual, but it seems an artfully artless presentation that nevertheless reveals its deliberate performance of democracy. White, on the other hand, with his awkward posing that’s partly casual (the hands behind the back, the everyday clothes) and partly rigid (the direct gaze, the precisely positioned hat), seems more “real.” Moreover, the geriatric’s unshaved face contrasts parallelly to Whitman’s carefully groomed beard. Likewise, for all the daringly open shirt, Whitman’s is immaculately clean, and his pants seem hardly aged or worn and instead prop-like. White’s hat, shirt, and pants seem to have undergone the actual stresses of everyday use. Finally, Whitman’s body is idealized: youthful, healthy, vibrant; White’s is aged, paunchy, decrepit. Whitman may gesture to his genitals with the pocketed hand, but White’s distended stomach seems (although unconsciously) more revelatory of a body that’s all too human. All of this has led me be–at least for the moment–critical of Whitman, a figure whom I’ve usually taught in almost exclusively celebratory fashions. The poet of democracy here strikes me as a “poser” in numerous senses of the word when juxtaposed against one of the perhaps more accurately average “roughs” of nineteenth-century America.

_-_1855_-_Da_front._di_Foglie_d%27Erba.gif)